In these respects, the legendary Diogenes would feel right at home today in many an American university, where a professed interest in human nature and human excellence–or, more generally, in truth and goodness–invites reactions ranging from mild ridicule for one’s naiveté to outright denunciation for one’s attraction to such discredited and dangerous notions.

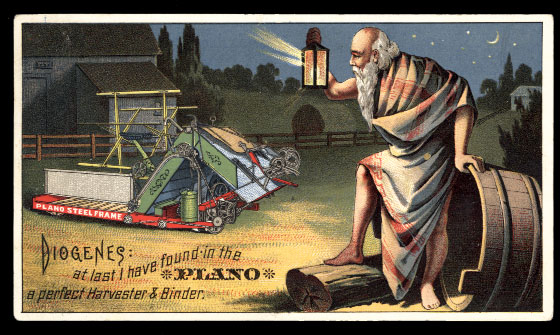

This same Diogenes, when he heard Plato being praised for defining man as “an animal, biped and featherless,” threw a plucked chicken into the Academy, saying, “Here is Platonic man!” These tales display Diogenes’ cynicism as both ethical and philosophical: he is remembered for mocking the possibility of finding human virtue and for mocking the possibility of knowing human nature. This lecture is, most of all, my expression of gratitude to the National Endowment for the Humanities and, especially, to the Republic of Letters for which it stands.Įveryone has heard the story of Diogenes the Cynic who went around the sunlit streets of Athens, lantern in hand, looking for an honest man. The point is not what I have learned, but rather what I have learned and, therefore, what anyone can learn with and through the humanities. Although the path I have followed is surely peculiar, the quest for my humanity is a search for what we all have in common.

#Diogenes quest pro#

I offer it not as an apologia pro vita mea, but rather in the belief that my own intellectual journey is of more than idiosyncratic interest. This lecture is, in part, an attempt to make sense of my adopted career as unlicensed humanist. Finally, perhaps because I am an unlicensed humanist, I have pursued the humanities for an old-fashioned purpose in an old-fashioned way: I have sought wisdom about the meaning of our humanity, largely through teaching and studying the great works of wiser and nobler human beings, who have bequeathed to us their profound accounts of the human condition. In addition, I have been willing to speak up in defense of our threatened human dignity, seeking to remind our contemporaries of forgotten truths that, in a more sensible age, would have needed no defense. I have also raised high the oft-abandoned banner of humanistic inquiry, and have tried in my teaching and writing to show its indispensable value for living thoughtfully and choosing wisely in our hyper-technological age. program, “Fundamentals: Issues and Texts,” which I chaired for many years, that emphasizes basic human questions pursued through the intensive study of classic texts. It is true that I have long been devoted to liberal education, and along with my wife, Amy Kass, and a few other colleagues at the University of Chicago, I helped found a successful common core humanities course, “Human Being and Citizen,” as well as an unusual B.A. I am but an amateur humanist, not only without great scholarly distinction but also without a license. For the fields in which I teach and practice, I have no formal training. What in the world could the Endowment be thinking? The fields for which I have trained, medicine and biochemistry, I neither practice nor teach.

Whilst a member of the NEH Council, I had helped to select six or seven of them, and I even had the honor of introducing Gertrude Himmelfarb and Leszek Kolakowski for their Jefferson Lectures. When Chairman Bruce Cole called last autumn to invite me to give the next Jefferson Lecture, my stunned silence covered a barely stifled “Who, me?” I knew well the roster of humanist giants who had gone before.

Now that this hour has arrived, I must finally accept the fact that tonight’s lecture is really mine to deliver. And I thank you all for your honoring presence here this evening. I am profoundly grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities for the great honor you have bestowed upon me. McClay, for your most kind and generous introduction.Ĭhairman Watson, members of the National Council on the Humanities and staff of the National Endowment for the Humanities, ladies and gentlemen.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)